Home » Pathologies » Ankle Surgery » Ankle Sprains and Ligament Reconstruction

Ankle Sprains and Ligament Reconstruction

A sprained ankle happens when the joint gets twisted sharply, causing the ligaments to stretch or tear. It usually affects the lateral collateral ligament. A sprain often happens when we trip on uneven ground or when playing sport.

Treatment involves physiotherapy, but if that does not work then surgery is recommended. The ligament is repaired using arthroscopic surgery to reconstruct the anatomy of the lateral collateral ligament.

Video presentation

Description & évolution

A sprained ankle is the most common injury in trauma medicine. Every day, one in every 12,000 people in France has one, that’s 6000 cases a day. It affects 1% of the global population every year. The worst sports for causing sprained ankles are basketball and handball. However, sprains are also common with tennis and football.

A sprained ankle happens when the ankle gets twisted accidentally, usually inwards (inversion of the foot). With a sprain, the ankle ligaments suddenly get stretched in the wrong direction and can even tear. The ligament damage can range from a simple sprain to a complete rupture.

Ligaments are like elastic bands that contain stretch receptors. In theory, when the foot starts to twist, the ligaments stretch and these receptors send a message to the brain, asking it to offset the risk of falling by reflexively contracting the ankle stabiliser muscles. This stops us from falling and spraining our ankle.

However, if the movement is too sudden, the brain doesn’t have time to act and the ligament stretches or even tears. This is called a sprain.

We’ve all heard someone cry out “I’ve twisted my ankle!!”.

What they’ve actually done is injured their lateral collateral ligament, a structure made of three bundles of fibres stretched between the fibula and the foot – the anterior bundle (anterior talofibular ligament, ATFL), the mid bundle (calcaneofibular ligament, CFL) and the posterior bundle (posterior talofibular ligament, PTFL). These bundles keep the foot in the correct position.

Lateral anatomy of the ankle

The clinical signs of a sprained ankle are pain and swelling on the outside of the ankle. Some patients can’t walk. They may feel a snapping sound, which can sometimes even be heard by other people nearby. They are apprehensive about walking and describe their ankle as “unstable”, as though it might “give way” at any moment. Later, there will be bruising (ecchymosis) beneath the outer ankle bone (malleolus) where blood is pooling under the skin.

Swelling and bruising of the side of the ankle

With a sprained ankle, the ligaments get either stretched, completely torn in the middle (mid-substance tear) or detached along with a fragment of bone. Depending on the severity of the injury and how it happened, one, two or three of the ligament bundles may be damaged.

In some cases, especially when the rotational force was very strong, the trauma can cause a fracture. It may also damage the cartilage in the ankle joint and the talar dome.

In terms of anatomy, a “serious sprain” is a complete tear of the anterior bundle of the lateral collateral ligament (+/- the mid and posterior bundles).

A diagnosis of sprained ankle should only be given once all other differential diagnoses have been ruled out (e.g. fracture, dislocated tendon).

Using certain clearly-defined criteria, an x-ray can be used to rule out a fracture of the malleolus or foot.

Emergency medical providers will check for signs of severity and arrange for further treatment or follow-up.

Emergency diagnosis and treatment

SIGNS OF SEVERITY :

Internal pain: damage to the medial collateral ligament (MCL), indicated by instability in the ankle.

Extensive haematoma: may indicate wider damage with potential bone involvement (bone oedema).

Initial inability to walk.

Just one of these signs indicates that the sprain is serious and requires stricter immobilisation.

TREATMENT :

1. RICE method :

Rest: Rest the leg to avoid further bleeding in the muscle or joint.

Ice: Ice causes the blood vessels to shrink (vasoconstriction) and slows down blood flow into the affected area.

Compression: Wrap an elastic bandage around the ankle to support the joint and help reduce the bleeding.

Elevation: Raise the leg above the level of the heart to reduce blood flow into the area.

This method can be used for both minor and major sprains.

With minor sprains, the ankle can be immobilised using a soft u-shape splint (sugar-tong splint) affixed with Velcro to prevent a further sprain in the first few days after the initial injury. The splint should not be worn for more than 10 days.

It is a quick, simple and adaptable way to provide rapid relief by stabilising the ankle joint. It provides local compression and some support, whilst still allowing the foot to point and flex but limiting inversion and eversion (the movement that caused the original injury).

After ten days, the patient can begin exercises with a physiotherapist and gradually stop wearing the splint.

With major sprains, a more rigid form of support is required. A walking boot is used. Plaster casts are no longer used. First, a boot avoids the need to give anticoagulants. Second, the patient is still able to move the leg muscles thus avoiding any major loss of muscle volume and tone. In fact, when a plaster cast is applied the muscles are forced to rest, so they shrink and become weak and when the cast is removed, they can no longer fulfil their role as secondary stabilisers of the ankle joint, making it much more unstable. The aim of the immobilisation is to rest the torn ligaments and reduce the swelling, in combination with a compression sock.

The primary goal of functional treatment is to allow the patient to walk again. They are encouraged to bear weight on the foot and walk as soon as possible after the sprain, if it is safe to do so. If the pain is too great, they can walk with crutches for a few days in order to lessen the weight on the ankle.

Functional treatment requires regular check-ups to make sure the ankle is healing properly and there are no complications. A check-up 8–10 days after the injury is essential to check progress and adapt the treatment. If after 10 days there is still any medial pain or the patient is unable to place weight on the injured ankle, the walking boot should be worn for longer. On the other hand, if the pain has subsided, they can switch to a smaller splint and physiotherapy can begin.

The major risk of a sprained ankle, even if not severe, is a recurrence: the rate of recurrence is particularly high with this type of injury and can even reach 70% among athletes, leading to chronic instability and early-onset osteoarthritis. In these specific circumstances, functional rehabilitation can help. It is the best way to lower the rate of recurrence.

2. Functional rehabilitation :

This is without doubt the most important aspect of treatment for a sprained ankle.

It should begin as soon as possible.

Most protocols use a combination of techniques to increase the effectiveness of the treatment.

- Reducing the pain and swelling: Massage, cryotherapy, manual or mechanical lymph drainage, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, ultrasound and other techniques.

- Regaining mobility:as soon as the pain allows. For the first few days, varus (inwards) movements should be avoided. These exercises will be used if mobility is not the same as on the healthy side, especially in dorsiflexion.

- Muscle recruitment:The sole aim is to prepare for neuromuscular reprogramming.

- Improving stability – Proprioception and neuromuscular reprogramming:After a sprain, the ankle may feel loose and unstable, or even sprain again. Neuromuscular reprogramming involves placing the patient in various unbalanced positions using different instability devices in order to trigger the body’s defence mechanisms.

NEUROMUSCULAR REPROGRAMMING

The length and frequency of sessions will depend on the patient’s progress. The treatment plan should be designed to allow the patient return to work and resume their social activities as soon as possible.

By tracking changes in various indicators (pain, swelling, mobility, strength, functional stability, activities of daily living), the practitioner can decide when to stop the physiotherapy based on targets that were predefined by the physiotherapist, doctor and patient. These targets should take account of the patient’s specific needs (social, professional and sporting activities).

If the injury worsens, the patient is referred back to their doctor.

Diagnosis & Surgical indication

The condition is usually easy to diagnose based on the obvious clinical presentation as the patient describes their many sprained ankles. They tend to be very anxious about walking on uneven ground or playing sports.

However, a particularly thorough physical examination is required in cases of subclinical dislocations with chronic pain. The surgeon should examine both ankles when the patient is relaxed. X-rays must be taken of both ankles, with an MRI of the injured side to look for damage to the ligaments (ATFL and CFL). The images may also reveal damage to the medial collateral ligament and talar cartilage (Osteochondral Lesion of the Talus, OLT). A joint scan could also be used to check for the same damage. Injections can then be given to relieve the pain caused by an unstable and inflamed ankle.

There are several scenarios for an unstable ankle :

RECURRING SPRAINS :

The patient presents with multiple sprains that do not respond to correctly-applied functional treatment or physiotherapy and requires surgery to prevent further recurrences and deterioration into ankle osteoarthritis. Treatment involves a ligamentoplasty of the ankle (a ligament graft).

UNSTABLE PAINFUL ANKLE:

With an unstable painful ankle, the patient complains only of pain with no feeling of the joint being sprained. The surgeon may use questioning and a thorough physical examination as well as further diagnostic tests to uncover evidence that the pain is due to ankle instability, despite the patient not being aware of it. A joint scan or MRI is needed to confirm the ligament damage. This presentation should be treated the same as multiple sprains. It can also cause cartilage damage and should therefore be treated the same way as an unstable ankle. Treatment involves restoring tension to the stretched ligaments.

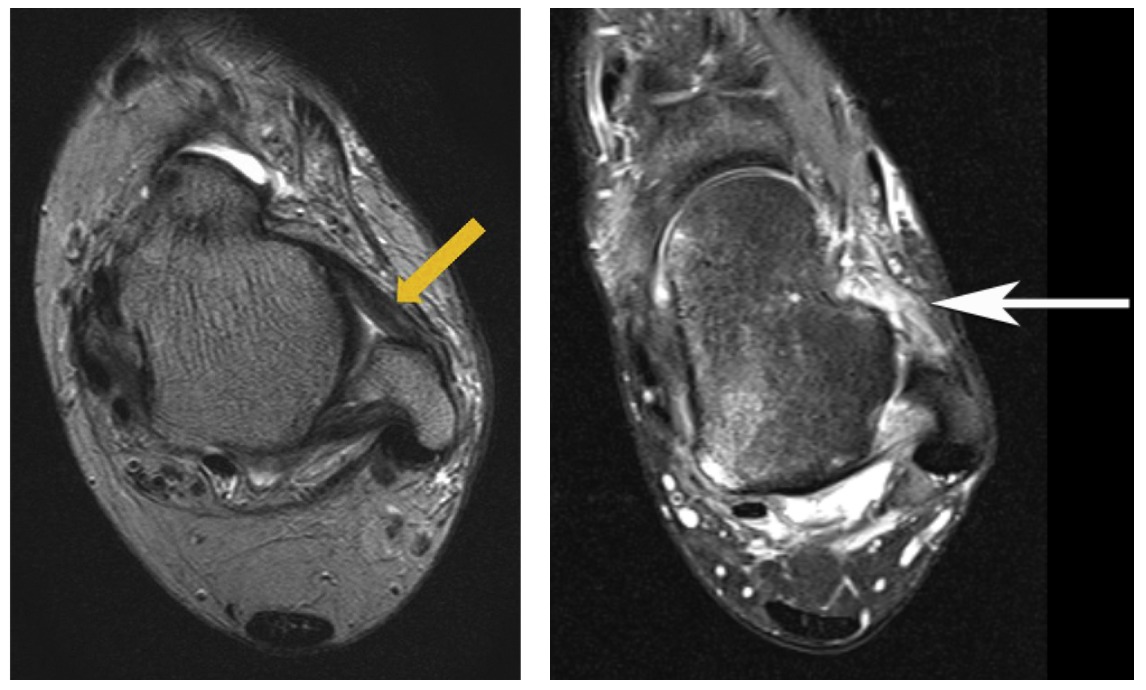

MRI of the ankle

NORMAL ATFL vs TORN ATFL

With most ankle sprains, the MRI will show greater or lesser damage to the lateral collateral ligament, but there won’t necessarily be any signs of instability. In case of doubt, dynamic x-rays can be obtained using a technique known as Telos stress radiography. This uses a device that places the ankles in forced varus and forced anterior translation to reveal any lateral and/or anterior instability.

If there is any pain and instability associated with a positive Telos test, surgery is required.

Ankle Telos

In both cases, the surgeon should consider surgery and decide between two possible treatments. Until very recently, both methods involved open surgery and invasive techniques. Nowadays, they can be done arthroscopically as an outpatient procedure. The operation either involves restoring tension to the ATFL and reattaching it to the bone (Brostrom-Gould procedure) or an anatomic ligament graft (gracilis tendon transplant) (see section on Hospital stay & procedure).

LIGAMENT REPAIR (BROSTROM-GOULD PROCEDURE) :

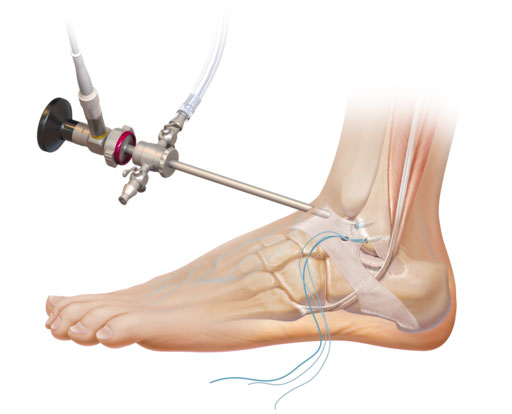

This procedure is performed arthroscopically, which means the surgeon does the operation by inserting a small camera into the joint. The aim is to restore tension to the Anterior Talofibular Ligament and reattach it to the bone using very tiny anchors. The surgeon makes three tiny 5mm incisions which will be invisible within a few months after the surgery.

ARTHROSCOPIC GRACILIS TENDON TRANSPLANT :

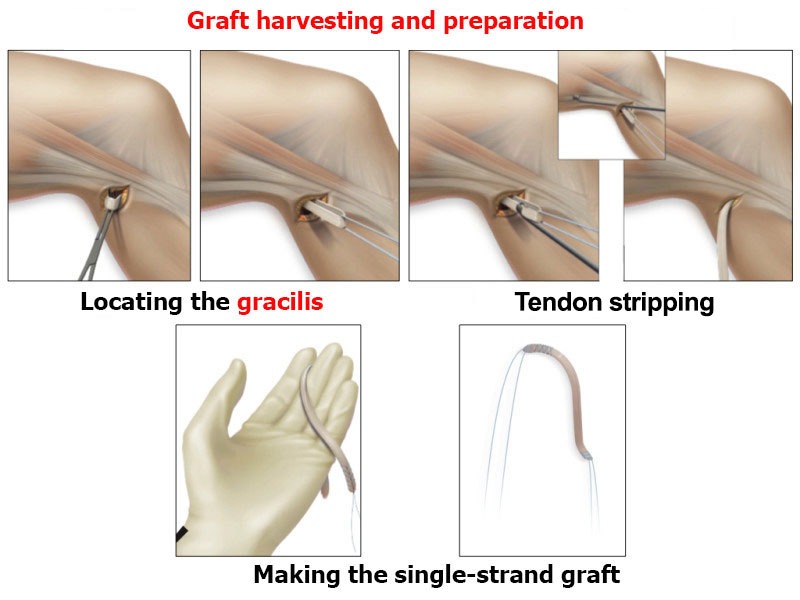

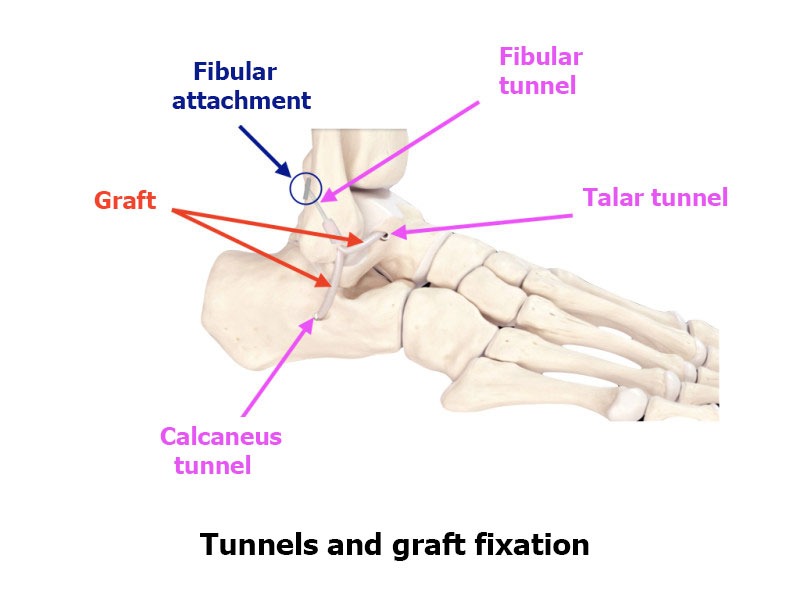

This procedure also uses arthroscopic surgery. The surgeon harvests a tendon from the thigh (the gracilis tendon) and uses it to reconstruct the Anterior Talofibular Ligament and Calcaneofibular Ligament by attaching it to the heel bone and the talus bone using two screws, and to the fibula with a cortical fixation device.

Preparing for surgery

SURGICAL CONSULTATION:

The aim of the preoperative consultation with the surgeon is to establish a diagnosis. With “detective-like” questioning, Dr Lévy should be able to retrace the history of the instability and identify how the first episode occurred. He will want to know how many sprains have happened and how (sport, work, daily life). He will ask if the patient has had any physiotherapy, and whether the number of sessions was enough. Dr Lévy will also want to know if the patient is bothered more by the pain or the instability. He will examine the ankle to check for apprehension when placed in forced varus. X-rays, MRI and a joint scan will be used to check for anatomic damage that could explain the instability. If necessary, dynamic x-rays (Telos stress radiographs) will be requested. Depending on the damage found, Dr Lévy will decide what treatment is required. He will explain what will happen during and after the surgery, as well as any potential complications. This will include a discussion of how long the treatment will last, the recovery time and any rehabilitation required after the operation.

You will be given time to discuss your options, and you will receive advice on the pros and cons of the surgery.

ANAESTHETIC CONSULTATION:

Once the indications have been confirmed, one of Dr Lévy’s assistants will give you an appointment with the anaesthetist who will look after you during the surgery. The anaesthetist will examine you and prescribe any additional tests that may be needed before the surgery. He or she will also explain how the anaesthesia works and the best method for you. The procedure is usually performed under general anaesthetic with regional top-up anaesthesia. You may however ask for it to be performed under locoregional anaesthesia.

SMOKING :

It is essential to stop smoking one month before and after the surgery. This is because a mass influx of nicotine reduces blood flow and slows down the healing process. You may use extended-release nicotine patches to help with the withdrawal symptoms.

Hospital stay & Procédure

The surgery will be performed as an outpatient procedure. There are two types of procedure for treating an unstable ankle. Dr Lévy will decide which one you need based on his examination and the results of the other diagnostic tests.

LIGAMENT REPAIR (BROSTROM-GOULD PROCEDURE) :

This treatment is only for patients who are suffering from pain caused by the instability, but without any actual sprains, and for patients who play little or no sports whose ligament is still in good condition. The ligament will have become detached from the fibula but not shrunk too much. This procedure is performed arthroscopically, which means the surgeon does the operation by inserting a small camera into the joint. The aim is to restore tension to the Anterior Talofibular Ligament and reattach it to the bone using very tiny anchors. Further support is provided using the extensor retinaculum (a fibrous structure around the ATFL). The surgeon makes three tiny 5mm incisions which will be invisible within a few months after the surgery. The patient can go home the same day with a walking boot to wear for 3–4 weeks. It will take 3–4 months before they can return to normal.

ANATOMIC TENDON TRANSPLANT :

This treatment is only for athletes or patients who experience major instability every day. It may also be offered to patients who suffer pain due to instability but when there is not enough remaining ATFL to reattach to the bone.

The surgery will be performed as an outpatient procedure. Dr Lévy performs the ligamentoplasty using the gracilis tendon. The graft is harvested using a short 2cm incision from the inside edge of the tibia.

The rest of the procedure is performed arthroscopically (guided using a camera). He makes tunnels in the calcaneus, the talus and fibula using special instruments. The tunnels are positioned exactly at the insertion points of the two anterior and mid bundles of the lateral collateral ligament. The transplant is fixed in placed using a resorbable screw in the calcaneus and the talus and using a cortical “button” in the fibula. These anchors keep tension in the graft until it has fused with the bone.

The main benefit of this arthroscopic surgery is the ability to check the entire joint and find and treat any other related damage (damage to the medial collateral ligament and or to the cartilage around the talus).

You will be able to get out of bed either the same evening or the next morning, depending on the time of your surgery. You will have to wear a walking boot for 3 weeks in order to alleviate the pain and avoid pulling on the stitches so they can heal. You can walk the very next day. Postoperative cryotherapy is important to limit pain and swelling after the operation.

This video demonstrates the procedure :

After the surgery

During the first month you will be allowed to walk as much as you like without limits. Rehabilitation will start as soon as possible, with the aim of restoring full extension in the joint. It will take longer to restore full flexion. The nursing team will also give you injections of anticoagulants (for 15 days) and change your dressings.

POSTOPERATIVE CHECK-UPS AND PHYSIOTHERAPY :

21-DAY CHECK-UP :

Until this appointment you will have to wear a walking boot DAY AND NIGHT and you should have already begun exercises at home to restore joint range. The swelling in the ankle will have begun to go down a little bit, and it will be less painful. Dr Lévy will examine the scar and your mobility and assess whether there is any residual pain. He will look at your new x-rays and make any necessary adjustments to your recovery plan for the next few months.

Depending on your recovery, you may be allowed to resume cycling (on an exercise bike) and swimming (kicking the legs only).

3-MONTH CHECK-UP :

The pain should in theory have completely gone, and you will be walking as normal without limits. You will no longer feel apprehensive about walking on uneven ground. Physiotherapy should have helped you recover the full range of motion in your joint, and you will have started muscle strengthening and proprioception exercises. You can start trying small jumps and landing in your physiotherapy sessions. If you have good ankle tone, you can now resume straight-line running on firm flat ground.

6-MONTH CHECK-UP :

Each ankle is different and Dr Lévy will give you specific advice on whether you can resume high-risk sports or whether you need to continue rehabilitation. In general, unlike with knee ligament surgery, you can resume all sports at this stage.

Recovery period & Return to work

You will be able to walk again immediately after an ankle ligament repair. You will need to wear a walking boot for 21 days.

The amount of time you need to take off work will depend on your job.

For office workers, this may be a matter of days.

For physical jobs or jobs where you need to stand all day, the average time off work is one month. This may be longer if the surgeon also had to repair the cartilage.

You can drive after 4–6 weeks (unless you have an automatic vehicle and use only the other foot, in which case you can drive after a few days). However, you may need to spend even longer off work if your job is incompatible with your recovery.

Potential complications

A wide range of complications can occur with surgery. Fortunately, they are very rare and the various appointments before and after the surgery are designed to avoid them or detect them early if they do appear.

As well as the risks common to all types of surgery and the risks of the anaesthesia, there are some specific risks associated with this procedure.

The following complications may occur with arthroscopic ligament reconstruction surgery :

SURGICAL SITE HAEMATOMA :

A haematoma is a rare but serious complication. It happens when there is bleeding from a small vessel in the ankle, filling the joint space with blood. The ankle swells and becomes painful and taut. If the cavity gets too swollen, the surgeon may have to perform a joint aspiration. If it happens again, it may require further arthroscopy to locate the leaking blood vessel and cauterise it.

SURGICAL WOUND INFECTION :

Despite all the precautions taken by the operating team, bacteria may still enter the wound either during the surgery or afterwards, before it is fully healed. This compromises the healing process (more redness around the wound than normal), causing very severe pain, a purulent discharge and a persistent fever.

You must tell the surgeon if you see any of these signs and seek emergency treatment.

Dr Lévy will decide whether to wash out the ankle and send any samples for testing, so he can prescribe the correct antibiotic for any infection.

PHLEBITIS/PULMONARY EMBOLISM:

Despite the preventive anticoagulant treatment given after the surgery and despite wearing compression stockings, a clot may still form in the leg veins (phlebitis) and require an effective dose of anticoagulant therapy for 3–6 months.

JOINT STIFFNESS :

This can develop due to inflammation (algodystrophy) and requires targeted physiotherapy. If there is still limited motion after three months, it could be caused by fibrosis which requires surgery to restore full movement.

COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME:

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, also called algoneurodystrophy, is a condition involving pain and other unpleasant symptoms in a joint after surgery or a fracture. The syndrome may have a neurological cause such as damage to the peripheral nervous system, affecting either the small fibres which protect from pain or heat stimuli, and/or the large fibres which detect tactile stimuli. It causes pain and severe stiffness that can last for up to 18 months. Patients always recover fully. Dr Lévy will diagnose the condition using scintigraphy (a scan) and will support you throughout, in order to treat the painful and unpleasant symptoms.

RE-TEAR :

The new ligament is almost equally at risk of tearing against as the ligament in your other ankle, especially if you resume the same sports.

This list does not cover all the possible risks.

Ask Dr Lévy if you want more information, especially if you have any questions about your particular situation and the advantages, disadvantages and risk/benefit ratio of each procedure.