Home » Pathologies » Shoulder Surgery » Acromioclavicular Joint dislocation

Acromioclavicular Joint dislocation

Acromioclavicular joint dislocation is when the acromion (top of the shoulder blade) separates from the clavicle (collar bone). The separation is caused by a fall onto the ‘point’ of the shoulder (rugby, judo, cycling etc.).

Treatment may be functional or surgical, depending on the extent of the separation. Surgery involves an arthroscopic procedure to stabilise the joint. Recovery is simpler than after open surgery to fix the joint with pins.

Video of the intervention

Description & progression

The acromion is the top edge of the shoulder blade. The joint between the acromion and the clavicle (collar bone) is called the acromioclavicular joint.

This joint is held in place by a capsule and the coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid), as well as by the deltoid muscle.

Trauma to the shoulder e.g. a direct impact (from cycling, rugby, judo etc.) can cause these ligaments to tear and the deltoid to become detached.

The acromioclavicular joint then becomes unstable and the acromion gets pulled downwards by the weight of the arm, whilst the collar bone is lifted by the muscles attaching it to the neck.

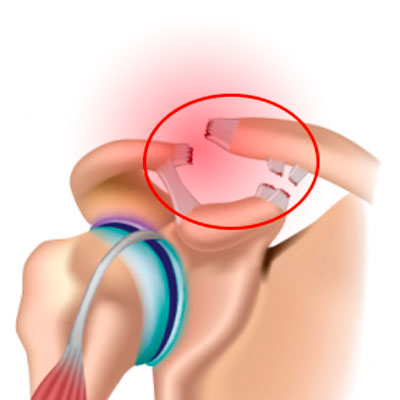

Any subsequent fall onto the point of the shoulder or contact during a match can cause pain and relative loss of function. An examination will look for the tell-tale “step” deformity.

Palpation will look for pain over the acromioclavicular joint, widening of the joint space and the “piano key” sign. Mobilisation will be used to perform the “drawer test” on the clavicle.

There are six stages of acromioclavicular joint dislocation, used to determine whether surgery is required.

A non-displaced sprain is usually classified as a benign injury. This clearly applies to stages 1–3, but much less so for stages 4–6. Some athletes such as rugby players can tolerate it, but others who do sports such as tennis and judo which require repeated use of the arm may find it particularly difficult to continue.

The injury can develop into chronic acromioclavicular joint disruption, where the shoulder has an unsightly and painful hump, with the pain radiating towards the elbow and often a loss of strength.

Some injuries may develop into post-traumatic acromioclavicular osteoarthritis, which causes pain when the shoulder is moved and is visible on an x-ray as joint impingement and cysts on either side of the joint.

This often requires open or arthroscopic surgery to release the joint and stop the painful bone impingement.

Surgical indication

The main system used for acromioclavicular joint dislocation is the Rockwood Classification.

Depending on the type of injury, this system ranks separations by degree of severity. It has six stages.

Stages I and II are classed as benign and require simple immobilisation followed by physiotherapy. The treatment for Stage III varies depending on the patient’s wishes and sporting activities. Stages IV, V and VI all require surgery.

SURGERY SHOULD ALWAYS BE PERFORMED WITHIN 15 DAYS OF THE TRAUMA.

Preparing for surgery

SURGICAL CONSULTATION:

The preoperative consultation with the surgeon often takes place on the emergency ward. The aim is to establish the diagnosis.

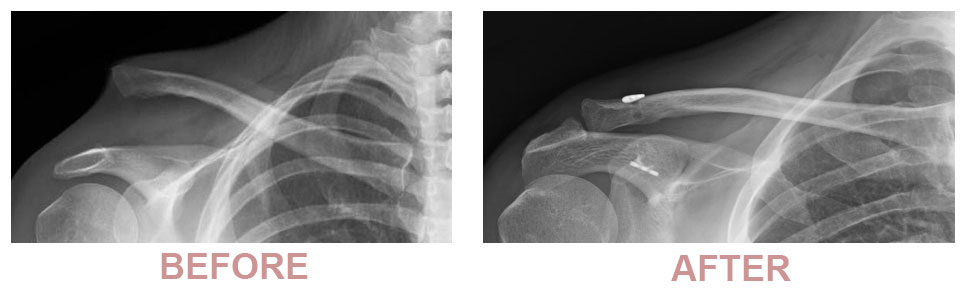

Dr Lévy will examine the shoulder to assess the damage to the acromioclavicular joint. He will use the “piano key” test and “anterior drawer” test to check the mobility of the shoulder. X-rays will be used to determine the stage of the separation. This information will be used to plan the surgery. Dr Lévy may also request a scan to see exactly how the clavicle has shifted. He will explain what will happen during and after the surgery, as well as any potential complications. This will include advice on the length of remission and when you can resume any sports.

ANAESTHETIC CONSULTATION:

Once the indications have been confirmed, one of Dr Lévy’s assistants will give you an appointment with the anaesthetist who will look after you during the surgery. The anaesthetist will examine you and prescribe any additional tests that may be needed before the surgery. He or she will also explain how the anaesthesia works. The procedure is always performed under general anaesthesia, together with locoregional anaesthesia to minimise any postoperative pain.

SMOKING :

It is essential to stop smoking during the month after the operation. This is because a mass influx of nicotine reduces blood flow, slows down the healing process and makes it harder for the tendons to fuse with the bones. You may use extended-release nicotine patches to help with the withdrawal symptoms.

Hospital stay & procedure

The surgery will be performed as an outpatient procedure. It usually takes about 45 minutes.

Surgery for acromioclavicular joint dislocation is done arthroscopically, which means the surgeon does not open up the entire joint but instead accesses it using tiny incisions less than 1cm wide.

Arthroscopy means none of the anatomic structures are affected, and he can access the joint without causing any trauma to the muscles or ligaments.

There are many proven benefits of this technique over traditional “open” surgery:

- Little or no visible scarring

- No muscle damage

- Faster functional recovery

- Little or no bleeding

- Less risk of infection.

Three tiny incisions will be made around the shoulder, each measuring 5–10mm. An arthroscope (tiny camera) is inserted into one of the incisions so that the surgeon can look at the whole joint. Very small instruments are then inserted into the other incisions to perform the surgery. A small 3cm incision is then made over the clavicle, for inserting the fixation material into the shoulder.

A pin is then passed between the clavicle and the coracoid (bony prominence of the shoulder blade) which will be used as an anchor to stop the clavicle from lifting.

A tension band is then attached to two points on the pin and used to hold the clavicle in place.

The procedure is demonstrated in the video below :

After the surgery

You should keep your arm in a sling day and night for one month after the surgery. If you are very careful or when taking a shower, you can remove your arm from the sling and hold it against your body. You should not raise the arm or actively move it away from the body. Dr Lévy will give you some exercises to do at home involving strictly passive movements, starting ten days after the operation. You should do the pendulum exercises every day. The actual physiotherapy will begin after your first check-up.

POSTOPERATIVE CHECK-UPS :

30-DAY CHECK-UP :

By this first check-up, the majority of patients say that the spontaneous pain has disappeared. You should still avoid sleeping on the shoulder but sleep on your back or on your other side. You can stop wearing the sling after this appointment. Dr Lévy will make sure the wounds are healing well and check your passive movement. An x-ray will be taken to check that the implant for stabilising the acromioclavicular joint is in the right place. You can start physiotherapy, initially with passive movements only, followed by assisted active then finally active movements. You must continue to massage the scars to prevent any subcutaneous adhesions from forming.

3-MONTH CHECK-UP :

At this appointment, Dr Lévy will check the range of motion in all sectors of mobility. It should have increased since the last appointment. By this point, you will usually be able to raise your shoulder between 90–120°. The scars should be soft and you can finally sleep on this side. He will prescribe you further physiotherapy to strengthen the muscles and continue improving your passive range of motion. You will find it easy to perform your day-to-day activities.

4–5 MONTH CHECK-UP :

By now the shoulder should be supple and pain-free. The shoulder will not quite have regained full strength, which will gradually return with physical therapy. You may resume light sports but should not begin any intense training until the surgeon gives you the go-ahead.

Recovery period & Return to work

The length of time you need to take off work will depend on your job and how you travel to get there.

You will not be able to drive for at least 30–45 days due to the surgery and the need to immobilise the shoulder for 30 days.

There is no reason why you cannot use public transport after a few days. Any work you do must be possible whilst wearing the sling.

You should wait about two months before resuming any manual labour.

If your job involves heavy labour you probably will not be able to return to work for four months. In principle, the shoulder should return to normal and you will not need to be reassigned to different duties at work.

Potential complications

A wide range of complications can occur with surgery. Fortunately, they are very rare and the various appointments before and after the surgery are designed to avoid them or detect them early if they do appear.

As well as the risks common to all types of surgery and the risks of the anaesthesia, there are some specific risks associated with this procedure.

The following complications may occur with shoulder surgery:

SURGICAL SITE HAEMATOMA :

A haematoma is a rare but serious complication. It happens when there is bleeding from a small vessel in the shoulder, filling the space beneath the collar bone where the operation took place fill with blood. The shoulder swells and becomes very painful and taut. If the cavity gets too swollen, the surgeon may have to perform further surgery to locate the leaking blood vessel and cauterise it.

SURGICAL WOUND INFECTION :

Despite all the precautions taken by the operating team, bacteria may still enter the wound either during the surgery or afterwards, before it is fully healed. Signs and symptoms of an infection are compromised healing with severe pain, more redness around the wound than normal, a purulent discharge and a persistent fever.

You must tell the surgeon if you see any of these signs and seek emergency treatment.

COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME :

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, also known as algodystrophy, is a condition involving pain and other symptoms usually in a limb following trauma or surgery, even if only minor. The syndrome may have a neurological cause such as damage to the peripheral nervous system, affecting either the small fibres which protect from pain or heat stimuli, and/or the large fibres which detect tactile stimuli. It causes pain and severe stiffness that can last for up to 18 months. Patients always recover fully. Dr Lévy will diagnose the condition using scintigraphy (a scan) and will support you throughout, in order to treat the painful and unpleasant symptoms.

IMPLANT MIGRATION :

This is a very rare occurrence that occurs when patients resume active movements too soon after the surgery or suffer an impact in the first month. The fixation material can come loose and migrate into the shoulder. A further operation is then needed to restabilise the clavicle with a new implant and is often performed as open surgery.

NEUROLOGICAL & VASCULAR DAMAGE :

This is a rare but serious complication. During the operation, the surgeon is working in close contact with the brachial plexus (the bundle of nerves supplying the arm) and the artery that supplies blood to the arm. In rare cases, fitting the implant can damage a nerve or blood vessel, causing pins and needles or a loss of feeling/movement, usually reversible. Any damage to an artery will have to be repaired by a vascular surgeon. Fortunately, this is rare.

This list does not cover all the possible risks.

Ask Dr Lévy if you want more information, especially if you have any questions about your particular situation and the advantages, disadvantages and risk/benefit ratio of each procedure.